The intent of the United States for invading Iwo Jima was to establish an airstrip for the purpose of attacking the mainland of Japan. Enitiwok was the staging ground for the military assault on Iwo Jima. Almost 900 African-American troops took part in the battle of Iwo Jima, including Sgt. McPhatter. On February 19 1945 Thomas McPhatter found himself on a landing craft heading toward the beach on Iwo Jima. McPhatter said, “There were bodies bobbing up all around, all these dead men,” said the former US marine, now 83 and living in San Diego. “Then we were crawling on our bellies and moving up the beach. I jumped in a foxhole and there was a young white marine holding his family pictures. He had been hit by shrapnel, he was bleeding from the ears, nose and mouth. It frightened me. The only thing I could do was lie there and repeat the Lord’s prayer, over and over.

Marine Sgt. Gene Doughty had the first squad of the 36th Depot as they landed on Iwo Jima. He recalls that they were four (4) all black Marine companies that landed on Iwo Jima, however, two (2) black companies that landed on D-Day; The 8th Ammo Company and the 36th Depot Company. Doughty’s squad of the 36th Depot received orders to guard the airstrip at Motoyama airstrip. On D plus five, Doughty saw the raising of the flag on Mt. Suribachi.

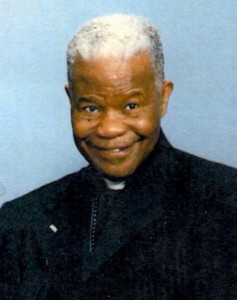

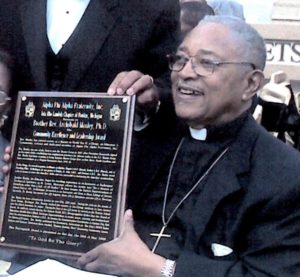

Marine Archibald Mosley was also part of the 36th Marine Depot Company were amongst the first to see combat and bullets on Iwo Jima. He says it was very difficult to dig a foxhole because after a small distance downward, the sand would just cave in and fill the hole you were trying to dig. This made troops highly susceptible to enemy fire. Being a part of a Depot company meant that Marines were carrying equipment, ammunition, and fuel which was the most dangerous thing in the world. One night Marine Mosley and his unit came under a Bonsai attack by the Japanese, killing a black marine (named Babyface) while he slept in his foxhole. Marine Mosley was awaked by his foxhole buddy (Wilbur) as he engaged hand-to-hand with the enemy. Marine Mosley, said while in basic training, members of his platoon had jeered him, because every night he said his prayers. Often he crawled into the sack sniffling because everybody was laughing and calling him a “momma’s boy”. However, on the night of the Bonsai attack, when “Babyface” was critically wounded, those very same individuals were begging him to pray for the fatally wounded Marine that everybody loved.

Marine S.L. Roberson, also saw action on Iwo Jima where black marines and soldiers of the U.S. Army in charge of transporting marines from ship (PA-33) to shore were killed outright by Japanese artillery and gunfire while performing their duties. Bodies floated in murky blood tinged ocean water on the beachhead, where lifeless bodies and body parts floated on the surface. Members of the Ammunition and Depot companies would take direct hits, blowing the bodies of marines and the equipment they had in tow up very high up in the air.

Montford Point Marines and the Raising of the Flag on Iwo Jima

Marine Sgt. Thomas McPhatter, (later a Vietnam, Lieutenant Commander in the US Navy), even had a part in the raising of the flag. “The man who put the first flag up on Iwo Jima got a piece of pipe from me to put the flag up on,” he says. Of course this is absent from history. Often Blacks and Native Americans were excluded from operational war photos for the purpose of promoting and selling U.S. Savings Bonds. “One of the marines said that the people who were filming newsreel footage on Iwo Jima deliberately turned their cameras away when black folks came by.

Melton McLaurin, author of the book entitled; The Marines of Montford Point, says that there were hundreds of black soldiers and marines on Iwo Jima from the first day of the 35-day battle. Although most of the black marine units were assigned ammunition and supply roles, the chaos of the landing soon undermined the battle plan. “When they first hit the beach the resistance was so fierce that they weren’t shifting ammunition, they were firing their rifles,” said Dr McLaurin.

Roland Durden, another black marine, landed on the beach on the third day. “When we hit the shore we were loaded with ammunition and the Japanese hit us with mortar.” Private Durden was soon assigned to burial detail, “burying the dead day in, day out. It seemed like endless days. They treated us like workmen rather than marines.”